Little did I know Koenig and her producers had no idea how to incorporate new evidence with their prior beliefs. They fell prey—repeatedly—to the prosecutor's fallacy, giving undue weight to new discoveries, trying to pull us along as they changed sides again and again. Unfortunately for them, the basic story never changed. At the beginning, there was no physical evidence against Adnan, and the whole case against him came down to Jay's credibility. In the end, there's no physical evidence against Adnan, and the whole case against him comes down to Jay's credibility.

Whenever Koenig was convinced of his innocence, something new—the Nisha call!—would change her mind. When she was almost convinced of his guilt, something different—the Aisha call!—would change it back. In the last episode, my frustration reached its peak when Dana—the "logical" one—summed up her understanding of the case with one telling instance of the prosecutor's fallacy. She argued that, despite the utter lack of evidence incriminating him, Adnan most likely killed Hae because the string of events that took place on the day of Hae's disappearance just make more sense that way, and are so unlikely if Adnan is innocent. I mean, if there's only a 10% chance that all of those unlucky coincidences would happen in the case of Adnan's innocence (the Nisha call, lending Jay his car and phone, asking Hae for a ride), then that means there's a 90% chance he did it, right??

Wrong. Turn that same argument on someone who wins the lottery. It's immensely unlikely, after all, for someone to win the lottery. But maybe she cheated. She's much more likely to win by cheating! There's only a 1/1000,000 chance of winning in the case of not cheating, so clearly, cheating is the more "logical" explanation.

The problem is with treating new pieces of evidence—winning the lottery, potentially unlucky coincidences—in isolation, rather than weighting them by prior likelihood. Yes, one is more likely to win the lottery by cheating, and yes, the Nisha call makes more sense if Adnan is guilty, but the prior probabilities in this case—of cheating at the lottery, of Adnan committing murder—are low. And that's what Koenig was missing throughout Serial, at every turn, in weighing evidence for or against Adnan.

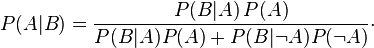

And of course, there's a foolproof way to incorporate new beliefs with old ones: Bayes' rule, the most misunderstood of mathematical truths.

Or

For instance, consider Dana's mental calculation at the end. She's looking at these coincidences more or less in isolation, as if they make up most of the case against Adnan (which, aside from Jay's questionable testimony, they kinda do). That is, she's considering the probability of Adnan's guilt (A) given the coincidences (B). Dana incorrectly equates this probability with P(B|—A), probability of B given not A, or the probability of those coincidences, given that Adnan is not guilty, which is of course low. Let's say 10% for the sake or argument. But as you can see, the two things are just not equivalent (this is the prosecutor's fallacy, more or less).

Let's estimate the other quantities reasonably. Let's imagine P(B|A), the probability of all of these unlucky things happening in the case Adnan is guilty, is high, say, 70%. (I wouldn't say 100%, even for the sake of argument, because why would Adnan call Nisha in the course of a murder?? All these things happening together is unlikely, even if Adnan is guilty).

Then there's P(A), the prior estimation of probability that Adnan murdered Hae, before we consider the evidence at hand. This has to be low, because Dana is using these coincidences to weigh Adnan's story against Jay's. And aside from that story, what reason do we have to believe Adnan committed the murder? Not much. So let's say this is 20% (still an overestimation, as well, I would say).

This leaves P(—A) = 1 - 20% = 80%, and our calculation is: (.7)*(.2) / [(.7)*(.2) + (.1)*(.8)] = .64

After weighing the evidence of these coincidences, our subjective probability that Adnan is guilty goes up, as we would expect. But not as high as we would think. Definitely not to 90%, as Dana kinda-sorta-implies but without any numbers. And I would argue that the 10% for P(B|—A) we chose was too low anyway, since we know Adnan had other potential reasons for lending his phone and car to Jay, and we know there are other possibilities for how the Nisha call could have happened. (And I don't know why they kept considering the cell tower evidence, since my understanding is that the tower just isn't that closely related to the location of the call).

This same process seemed to take place over and over again in Serial. Something new would come up, and Sarah Koenig would overstate its significance. Adnan stole money from the mosque: maybe he has the personality to commit murder. Aisha called Adnan when he was high at Jen's house: Adnan had a reason to be acting scared of the police. These may have made for compelling drama early on, but ultimately, turned Serial into a frustrating experience, because after the first few episodes, nothing of any substance happened or changed. The case against Adnan was comically thin all along, and the producers of Serial failed to break the story down much further than that.

In the end, it all came down to your P(A), your estimation of the prior likelihood of Adnan committing the murder after considering the basic evidence, and so everyone's opinion pretty much lined up with whom they believe more, Adnan or Jay. And in that sense, the whole series was a massive exercise in confirmation bias.